I posted a picture photo to Instagram last evening, I tell. There were so many things to consider. Were the light and position flattering? Have I exhibited my positive part?

She laughs. “I do discover it fascinating”, she says, “this entire history of taking a picture in a camera. You can see how a child’s posed, the approach they’re holding the camera. There can be different clothes every morning, but you’re usually in your floor. In some ways, it turns into a philosophical photo project. It’s funny.”

It’s a crazy experience, discussing appetite nets with the person who pioneered the selfie. We meet at the Museum of Cycladic Art in Athens, Greece, where an exhibition of Sherman’s earliest runs has just opened. It’s 40 deg and tropical – yet the Acropolis has shut for the day. But sitting across from me in an show room, the 70- year- ancient is quickly cool and stylish. She wears a bright Loewe T- shirt, white pants and Prada sneakers, her silver hair pulled back into a lower hairstyle. She is very accommodating, form, and soft spoken, as you might assume from someone with her level of success.

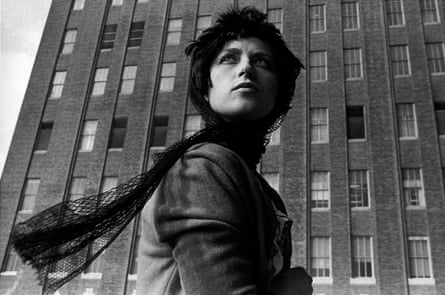

To suggest that Sherman redefined portrait photography is an exaggeration. Her signature practice – transforming herself into characters from saints and imperilled secretaries to grotesque clowns and elderly “ladies who lunch” ( acting as her own makeup artist, hairdresser, stylist and director ) – has influenced countless contemporary portraitists. She claims that her photos are “lies” and that she is frequently attempting to “erase” herself to fit stereotypes of women in film, advertisements, and television.

Which is not that far removed from cultural advertising, I say. Do we all these times project distorted images? She responds, “I certainly believe technology is changing the world best today.” I can’t imagine growing up with social media. A young person must have to manage all of that without coming off as so self-conscious. One’s a content publisher presently or wants to be an celebrity.”

The show, Sherman’s primary in Greece, brings together more than 100 of her earliest functions. It includes her milestone set ( 1977- 1980 ), which consists of dozens of charcoal- and- light photographs inspired by 50s and 60s Hollywood, film noir, B- movies and Western arthouse cinema. Sherman captured herself evoking library, rednecks, seductresses and more. She is Sophia Loren, Brigitte Bardot, Marilyn Monroe and Anna Karina– though her characters always have titles, united solely by their rebellious refusal to follow agreement.

She imitates a method used by film-makers like Alfred Hitchcock in a 1980 television series, Rear Screen Projections, by filming herself and her history singly and gluing the two pictures together.

Sherman recalls her first work, saying, “I was more pleased or influenced by films than physical art. I was thinking: ‘ Why would she be in that condition, doesn’t she realize it’s hazardous?’ Being a young lady who was a vulnerable young woman who was moving to New York, where you felt the awkwardness and despair of a big city, was also a way to control. It was a way to perform- work trust.”

Sherman was raised on Long Island. Her father was an expert for the Grumman plane firm, her mother was a tutor. She studied skill at Buffalo State University, where she grappled with her fear. She would dress up and pose in costume in a part of a party while wearing makeup and clothing from thrift stores. Her distinctive musical voice began to emerge after her then-boyfriend suggested she file her transformations. She discovered that painting was “so much faster” and philosophical than painting.

So she left New York at age 23 and continued to question women identities and children’s roles in society using style, prosthetics, and technology over the years. She has become something of a bizarre secret because of how many different figures she embodies. When, in 2012, several attendees believed they had seen her it in illusion: one claimed she was wearing wire-rimmed spectacles, and another claimed she had come in a large match.

“It was absolutely not accurate, but it was interesting to me”, she says, smiling.

Where did her need to dress up stem, I ask? She says, “It’s really related to my upbringing as the youngest of five kids,” with the ease of self-awareness of someone who has gone to therapy. There was a nine-year distance between me and the second child and the oldest, who was 19 years apart. I realized that my home lived a completely different life before me. To me, it resembled a story.

“In the end, I thought maybe they didn’t want me the way I was, so I should try to be a different person. Back then, many young women played dress-up. But instead of trying to become a lady or a fairy, something sweet and romantic, I was constantly trying to be a monster, a witch or older lady.”

The museum is presented at a time when. The museum wanted to show how Sherman has criticized society’s portrayal and treatment of women, and the museum also has BC that scholars have interpreted as depictions of a feminine god associated with reproduction and rebirth.

Whether it’s her set Color Studies, which shows people in secret events, or Centrefolds, which links romantic images from men’s magazines, her photographs centralise the female figure. This has sometimes proved divisive. Because the women in Centerfolds look melancholic, vulnerable or fearful, New York magazine critic described them as the “unsexiest sexy pictures ever”, while some feminists condemned them as titillating.

“I see my work as feminist but I don’t see it hammering a message over somebody’s head,” Sherman says, “It’s subtle, because I’m a subtle person. I don’t think I would be a good opponent for debate. I’m very bad at quoting things or citing whatever person’s opinion. That is related to the absence of a title for the pictures. I think everybody’s going to interpret things differently, and I can’t control how somebody’s background in art history is going to affect how they see my work.”

Nonetheless, the debate around Sherman’s work made her a sensation. Untitled #96 from Centrefolds sold at auction for $3.89 million in 2011 for the most expensive photograph ever made at the time. She has also received countless awards including a MacArthur Fellowship “genius grant”.

“Does she believe that the representation of women in the media has improved? I believe that women are more aware of their place in society, their rights, and power, or lack thereof,” she says. They are also more aware of how society views us and how we try to conform to our expectations. But it’s hard to know. Young people trying to figure out their place in society can be harmed by the entire selfie culture, as well as the selfie tools that automatically correct skin tone or get rid of imperfections.

However, Sherman enjoys playing with some of these resources herself. In recent years, she has been utilizing apps and AI to distort her features. She makes a good observation about the dissociative nature of social media by making an appearance quite strange in each of them. I do find it very fun, actually. “But I’m a little frustrated now because whenever I’ve tried to make a new image for Instagram, I feel like it’s not new enough.”

I tell her that the fact that she once had to go through the entire process of styling herself and can now just press a button is both amusing and frightening. Is she concerned about the danger that AI poses?

“I definitely see the threat that it could become, especially with those deepfakes. But whenever I’ve typed in something like, ‘Middle aged woman, alone in a forest, in the style of Cindy Sherman’, what they come up with is so not a threat to me that I just laugh at it. It’s such a bad version of my work. But some of the faces I’ve created from AI are fantastic. It helps me think differently about what’s possible.”

These days, Sherman is trying to figure out her “next steps.” “I don’t feel like I’m going to retire, but ageing changes the work,” she says. “When I was younger I could play young and old characters, now my range is limited.”

She’s been through many iterations, not just professionally but personally too. Before dating film-maker Paul H- O and musician, she was married to the video artist Michel Auder for 17 years ( he struggled with heroin addiction ). Today, she’s enjoying the sights of Athens with her new partner.

Which reminds me, has she listened to Billy Bragg’s song about her,”? Yes, I was very flattered, especially since we’ve never met. However, I believe there is a little bit of a difference between our lives.

And with that, we take a selfie together, and say goodbye.