In principle, apps for selling next- hand clothes for as Vinted, Depop, ThredUp and Schpock offer an opportunity to get both cautious and stylish. Great for customers who are concerned about rising prices and the sustainability of purchasing new clothing.

Second- side markets like these, and their in- person iterations like charity shops, have long been lauded as a more knowledgeable, honest, and socially responsible shopping choice. However, our research has revealed that these areas conceal the problems that our use causes. They offer merely individualised, wholesale answers to the great global issue of waste.

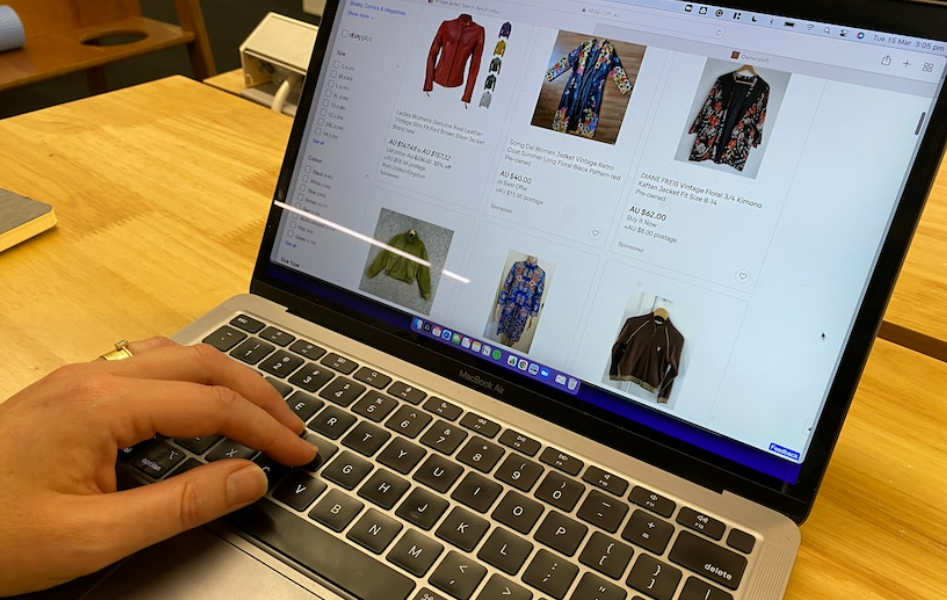

More people are selling their ancient clothes online using Facebook, online sites like Depop, and companies like Airobe. ( ABC News: Darryl Torpy )

More people are selling their ancient clothes online using Facebook, online sites like Depop, and companies like Airobe. ( ABC News: Darryl Torpy )The ’round market’ is failing

The” spiral economy” created by programs that sell “pre-loved” clothing as a means of prolonging the life of clothing and other consumer products is a topic of conversation in business circles. These apps, like other online selling markets like Facebook Marketplace and online, adhere to the commonsense concept of the circular economy because they let unwelcome goods move through the system rather than being toppled up the garbage.

A really circular economy should not only discard products, but also stop the development of waste in the future. And by that measure, clothes areas are failing brilliantly. By 2030, more than 100 million tonnes of new clothes will be produced annually, according to a document from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, which will increase our global production of climate change by more than all other industries combined. Second-hand distributing is failing to address the inexplicable scale of textile production on the global market.

Second- hands searching doesn’t make a thorn in the range of clothing manufacturing worldwide. ( Pexels: Cottonbro )

Second- hands searching doesn’t make a thorn in the range of clothing manufacturing worldwide. ( Pexels: Cottonbro )There are a few reasons why we criticize second-hand places. Second, buying and selling second- hand gets talked about and even advertised as what good, sophisticated, thrifty people do, specially under rising costs of living. Reselling apps, donations to and purchases from charity stores, create a “warm warmth” that helps to make up for the insecurity of purchasing new things.

But most considerably, next- side markets are built to raise consumption, not cut it back. Charity stores, for example, under increasing pressure to become successful, have to take on more professionalised and” for- income” branding practices. Even luxury goods retailers have embraced the popularity of second-hand shopping because it expands their market and allows for future customers to access their products.

The majority of second-hand clothing still ends up in the world’s south.

The second- hand myth of “shopping for good” disguises a mountain of problems. –

Only 10% to 20% of the donations made to charities and donated to charity shops are suitable for sale. The remainder are recycled or returned for resale in developing nations in the south of the world, creating a multi-billion dollar industry supported primarily by charitable organizations. The majority of shoppers and those who donate their clothes are unaware that this is occurring.

This redistribution of subpar, unsold goods from the west to wholesalers in countries like India, Senegal, and Nigeria can undermine local manufacturers and stow local businesses out of business. The sheer volume of textiles means that often huge swaths are dumped or, worse, openly burned on the streets, polluting the air with chemicals. In addition, the demise of ( mostly cheap synthetic ) clothing pollutes waterways with microplastics and releases toxic gases.

As depicted in the short film Unravel, the dangerous work of picking through such waste for the purpose of recycling is primarily carried out by women and people in marginalized groups. Based on an anthropological essay by Lucy Norris, the film explores the conditions under which women in northern India work to shred and turn unwanted western clothing into yarn.

Exploiting vulnerable groups ( including children ), and putting the health and safety of workers at risk are the characteristics of many “solutions” that promise to deal with waste from the West. While second-hand consumption provides a practical solution to the issue of accumulation, recent celebrations of the “circular economy” only support the constant flow of goods through our homes rather than stop it.

Instead of relying on the individualized solutions offered by the second-hand market, we should instead consider collective strategies. This might involve showing solidarity with and getting reparations for those who are most directly impacted by the negative effects of second-hand markets, for instance by supporting organizations like the OR Foundation in Ghana or The Association of Ragpickers in Bengal. Making brands accountable for the entire lifecycle of the products they produce may be a part of this.

In the end, holding manufacturers and governments accountable for their inactions in terms of the environment and human rights is ultimately the only viable response to the global waste crisis.